A shameful lesson for Black History Month of faltering medical ethics, forsaking the Hippocratic oath, and promoting medical racism through the Tuskegee Syphilis Study.

In light of Black History month, I want to share some thoughts about how medicine is different and better because of the contribution of Black Americans. It also allows me to reflect on what can be done to improve medicine as a profession to serve more people and allow them to thrive at their best.

I think if you ask almost any doctor what Tuskegee means to them, you will find them cast their eyes downward in shame. Why? Because we have been taught about the Tuskegee Syphilis Study and learned principles of medical ethics using this as a case study of what NOT to do.

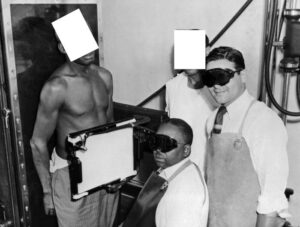

Tuskegee Syphilis Study on African Americans offered as free medical treatment

Tuskegee is a town in Macon County, Alabama that was originally inhabited by the Creek Indians. Then it became known for its cotton plantations. From 1932-1972 the United States Public Health Service funded a study on the natural course of untreated syphilis.

At the time the study began, it was not known that antibiotics could cure syphilis, but it was known that mental illness and death could result from untreated syphilis. By promising research subjects free medical treatment, they enrolled approximately 400 Black men who had syphilis and compared them with similar men who did not.

Withholding penicillin known to be effective against syphilis – for decades

Initially they were given heavy metal treatment, which was standard, but by the 1940s (within eight years) it was known that syphilis was better treated with penicillin. However, the men were not offered penicillin or even told that the spinal taps that were done to study the course of disease were not therapeutic.

Every 4-6 years starting in 1936, results were published for medical review, and yet the study was not stopped until 1972 when the results were made public through the national press and there was a national outcry about the inhumane treatment these men received. In 1974 the HEW (Department of Health, Education, and Welfare) stopped the study and subsequently passed the National Research Act that set up the IRB (Institutional Review Board), requiring that any study involving humans be reviewed for its ethical standards.

No informed consent, and “do no harm” from the Hippocratic oath goes out the window

The tragedy of this study is that there was no informed consent to participate and the health and welfare of the patients were not considered. Patients were marginalized and taken advantage of in order to further research.

The precious Hippocratic oath to “do no harm” was blatantly disregarded when a better treatment became available that could have been used to stop the course of the disease. Countless men, their sexual partners, their families and their communities suffered because of this. It also “laid a foundation of distrust”(1) of the medical community.

These men contributed to our understanding of a disease, but more importantly contributed to our understanding of how NOT to run a research study and how to make sure that doctors and researchers are protecting and looking out for the best interest of their patients.

I am hopeful that we as doctors and researchers will never fall to such a depth of character in our quest for knowledge again. I owe it to my patients and to future generations to practice medicine in a truthful and open way – explaining what we know and what we don’t know, and making available the best medical treatment.

The Tuskegee Study can change the way Americans view illness

I will close with a quote from James H. Jones, a historian and specialist in bioethical issues who wrote “Bad Blood: The Tuskegee Syphilis Experiment.”(2)

“As a symbol of racism and medical malfeasance, the Tuskegee Study may never move the nation to action, but it can change the way Americans view illness. Hidden within the anger and anguish of those who decry the experiment is a plea for government authorities and medical officials to hear the fears of people whose faith has been damaged, to deal with their concerns directly, and to acknowledge the link between public health and community trust. Government Authorities and medical officials must strive to cleanse medicine of social infection by eliminating any type of racial or moral stereotypes of people or their illnesses. They must seek to build a health system that will make adequate health care available to all Americans. Anything less will leave some groups at risk, as it did the subjects of the Tuskegee Study.” (p. 241)

(1) The Tuskegee Syphilis Study and Its Implications for the 21st Century

(2) Jones, J. H. (1993). “Bad Blood: The Tuskegee Syphilis Experiment”, New York: The Free Press (1993).