Baby Liam Burke is just learning to crawl. But he was conceived when Bill Clinton was president, the World Trade Center stood tall and home computers had the newfound ability to dial into something called the World Wide Web.

Suspended 19 years in deep freeze, Liam is the beloved new son of Kelly Burke — and one of the oldest embryos ever thawed and restored to life.

“He is the most awesome baby there is,” said Burke, 45. “He is a happy, healthy baby, a little bundle of joy, smart and interactive.”

What’s more intriguing, Liam is adopted. An Oregon couple who had twins two decades ago through San Ramon’s Reproductive Science Center kept his embryo frozen for years, keeping open the option of expanding their own family. Ultimately, they decided to donate the embryo to Burke for her own pregnancy — a profound example of technology’s extension of life.

Like Liam, about 10,000 embryos a year are thawed and join families, thanks to advances in the field of cryopreservation. Others linger, sometimes for a decade or more, raising medical and ethical dilemmas never imaginable a generation ago.

Infertile couples create embryos using in vitro fertilization, which joins eggs and sperm in a Petri dish. They typically create as many as possible to maximize their chances for parenting — but if the first attempt results in a baby, other embryos are left over.

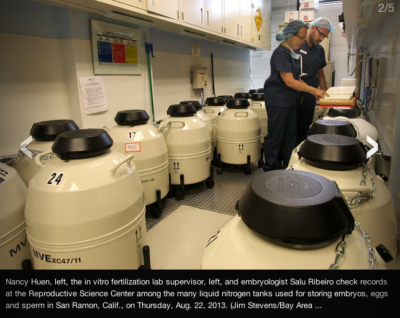

In 1985, there were 285 frozen embryos in the entire nation. Now an estimated 400,000 to 600,000 human embryos live as souls on ice, carefully held in liquid nitrogen tanks.

Of these, about half will eventually be implanted into their mothers, according to ReproTech, a company that specializes in long-term storage of embryos for $400 a year in its facilities in Nevada, Minnesota, Texas and Florida.

Most of the rest are discarded or donated to research.

A lucky few — 1.5 percent — are, like Liam, gifted to women like Burke.

A lucky few — 1.5 percent — are, like Liam, gifted to women like Burke.

The research scientist at NASA in Hampton, Va., has five university degrees — two bachelors, two masters and a doctorate. Education deferred her dream of motherhood, then her own attempts at in vitro fertilization ended in two heartbreaking miscarriages.

But she’s a big believer in the power of science to solve problems, and she held out hope.

“Technology is my world,” she said.

Locating Liam proved much harder. For emotional reasons, doctors say, few couples are willing to surrender their embryos.

Burke was pursuing adoption when her attorney discovered the Oregon couple — with college-age twins — finally had decided not to use their saved embryos. The couple are not named to protect their confidentiality.

“They decided they wanted to give those embryos a chance at life,” Burke said.

She began an application process, assembling a portfolio — describing herself and her struggle to create a family — that she hoped would make her stand out among the many applicants. Then, over the next four months, by email and phone, she answered tough questions about politics, spirituality and her views on education. They agreed to an open adoption, which means Liam will get to know the couple who gave him life and his siblings.

Last year, Burke flew from Virginia to San Ramon for the procedure.

It ended in joy: Liam, born last November in a natural birth, weighed a robust 8 pounds, 5 ounces.

“I was so grateful,” she said. “One of the reasons I’ve gone public is to give people hope. I hope to help people consider the option of donation.”

Freezing embryos has gained popularity because of its many advantages, said Seattle Reproductive Medicine lab director David Ball, a spokesman for the American Society of Reproductive Medicine.

Rather than subjecting women to surgery each time they need to get an egg, doctors now retrieve a dozen or more eggs at once. They can be implanted in the womb one or two at a time — or saved indefinitely. The San Ramon center has one embryo it estimates is 27 years old.

Rather than subjecting women to surgery each time they need to get an egg, doctors now retrieve a dozen or more eggs at once. They can be implanted in the womb one or two at a time — or saved indefinitely. The San Ramon center has one embryo it estimates is 27 years old.

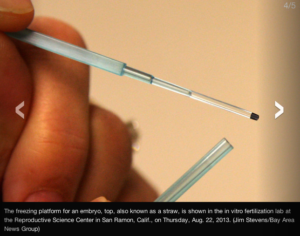

What transformed the practice is a flash-freezing innovation called vitrification, which cools the embryos so quickly that their water molecules don’t have time to form ice crystals, which could slice delicate cells like a knife, said Burke’s physician, Dr. Deborah Wachs, a reproductive endocrinologist.

Scientists also have discovered the optimal age for freezing: five days after fertilization, when the embryo has grown to 150 to 200 cells.

The embryos are transferred into thin straws that are suspended in liquid nitrogen freezers and preserved at minus 196 degrees Fahrenheit, Wachs said. At this temperature, growth literally freezes to a halt.

“It’s not generating, it’s not degrading, it is suspended in time,” Wachs said. When thawed, “it becomes big and plump.”

Scientists can also cull the weak from the strong, selecting those embryos whose cells are most tightly packed — boosting the odds that it will survive the long nine months to birth.

Extensive paperwork is completed before the fertilization, to answer tough questions: If a couple divorces, should the embryos be divided up, like silverware? What if a couple die, move away or declare bankruptcy?

Embryo abandonment is a problem every clinic faces. As long as the freezer bill is paid, the embryo is safe — for years, decades, maybe generations.

That growing longevity on ice raises an ethical issue. “Imagine in a thousand years someone doing IVF with a long-frozen embryo just to see what a 21st century — or, in this case, 20th century — human being was like,” said Hank Greely, director of Stanford University’s Center for Law and the Biosciences. “Just keeping them frozen — kicking the can down the road a little farther — seems wrong to me. Use them, destroy them, donate them for research, or donate them for adoption. But make a decision. If you keep putting it off by keeping the embryos in liquid nitrogen limbo, who knows how they may eventually be used?”

Someday, Liam will be told about his fortunate journey, “when he’s old enough to understand,” Burke said.

He’ll meet his siblings, 19 years his senior. And perhaps one day he’ll meet a younger sibling or two. Two of the couple’s leftover embryos remain frozen in San Ramon, preserved for an unknown future.